April 4, 2023

The U.S. Supreme Court should issue a ruling soon in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. This is the latest Supreme Court case to examine copyright law and the doctrine of fair use which, together, are supposed to both encourage the creation of art by ensuring creators own (and are paid for) their work while also allowing others to use existing works to create new ones. The stakes are high because the potential creative and financial ramifications are huge.

Following up on the previous blog post: how did it all come to this?

The most straightforward answer is that we got here by judges (trying) to make principled decisions about when borrowing is fair use and when it’s infringement. With visual art, to put it mildly, this is tricky.

By way of example, according to the Second Circuit, this:

is fair use of these:

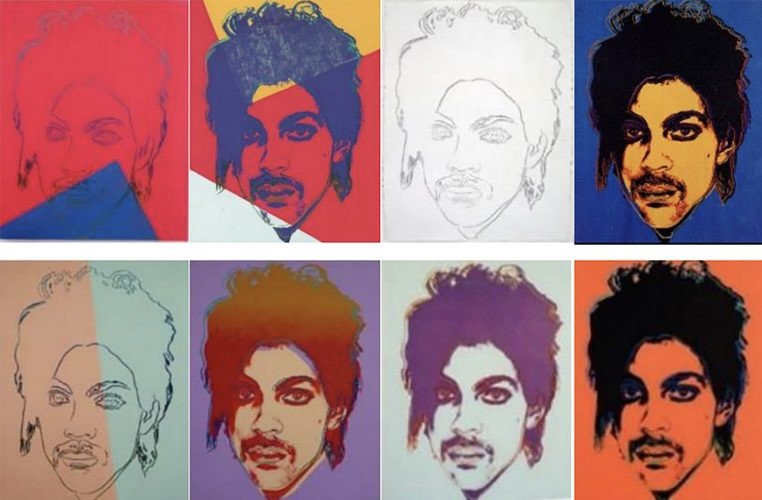

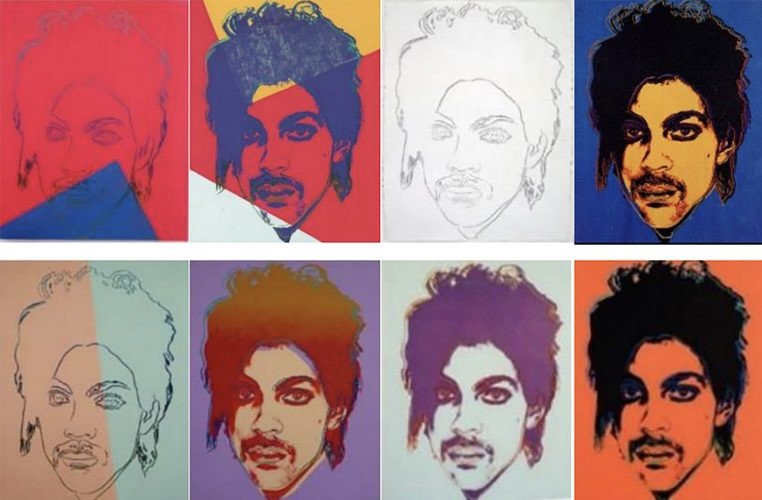

but, these:

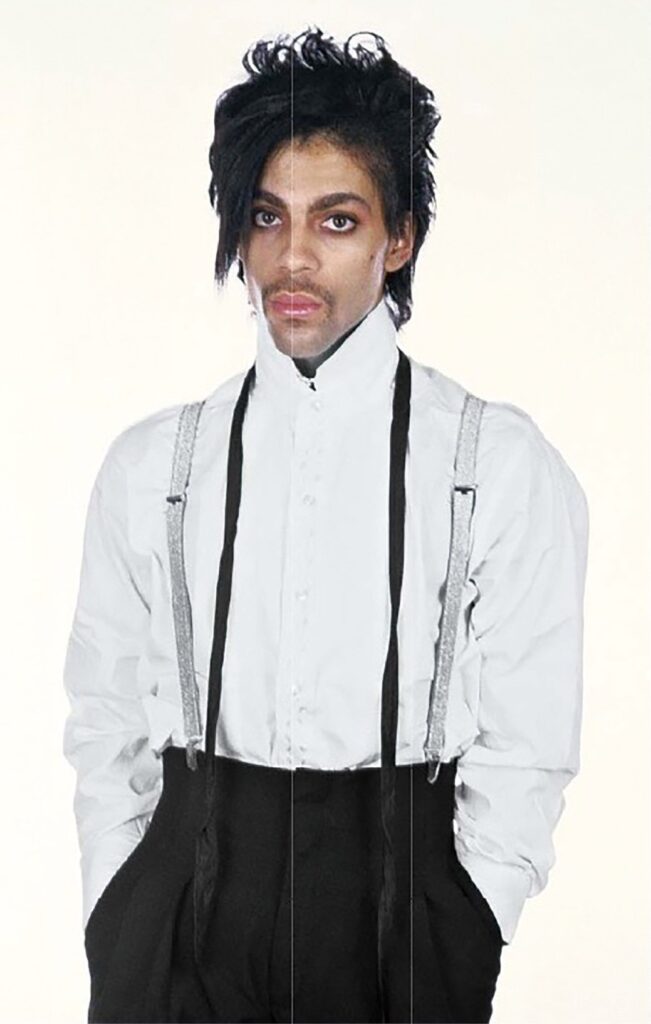

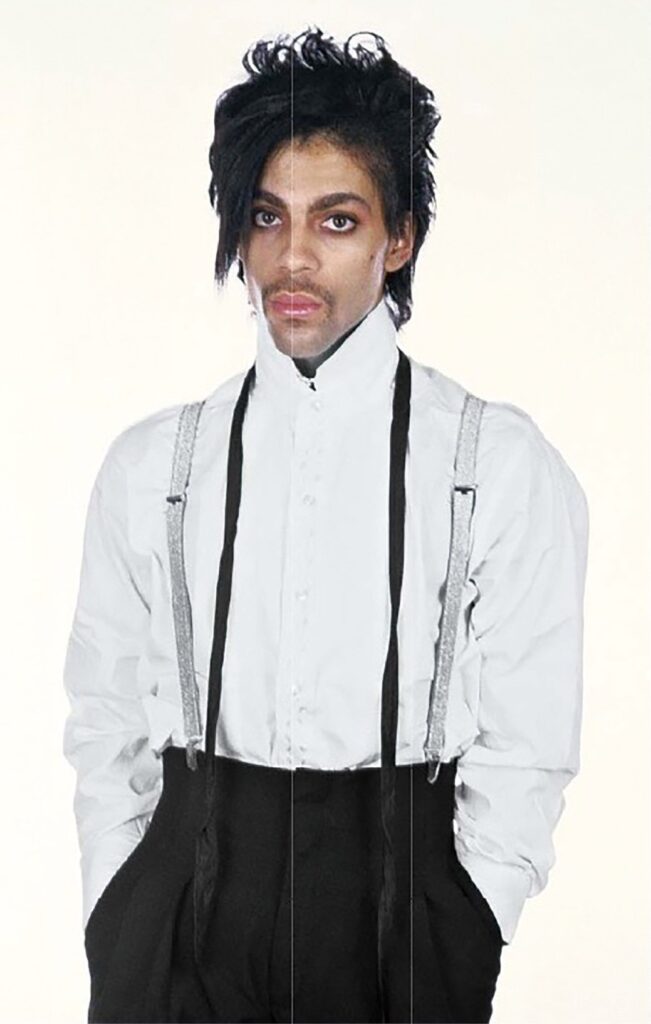

which incorporate this,

are not.

The first set of images comes from Cariou v. Prince, a case in which photographer Patrick Cariou sued “appropriation” artist Richard Prince over 30 artworks Prince created that included elements of Cariou’s photos of Rastafarians. The Southern District of New York ruled in favor of Cariou, holding that Prince’s works were not fair use because they didn’t comment on or criticize Cariou’s photos.

The Second Circuit disagreed. It found that the District Court imposed an incorrect legal standard by requiring Prince’s work to comment on Cariou’s work.

Instead, the Second Circuit emphasized that to constitute fair use, the later work must “alter the original with “new expression, meaning or message.” The Second Circuit took this standard from a 1994 Supreme Court case, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., which involved 2 Live Crew’s adaptation of Roy Orbison’s song “Pretty Woman.” In particular, the Second Circuit held that Prince’s artworks had an “entirely different aesthetic from Cariou’s photographs.” Based on this, the Second Circuit concluded that 25 of Prince’s artworks were sufficiently transformative to constitute fair use (the question of the remaining five works was remanded to the District Court).

In reaching this conclusion, the Second Circuit said that it shouldn’t be read to suggest that any cosmetic changes are enough to mean that something is fair use. Rather, it emphasized the fact that Prince’s images had “a fundamentally different aesthetic” than Cariou’s photos.

While that certainly appears to be true in Cariou, it also may be true in Warhol v. Goldsmith — as the Warhol Foundation has argued — that the Prince Series has a very different aesthetic from Goldsmith’s portrait of Prince. But how do artists (or lawyers or judges) determine how much transformation is enough to put them in the clear? Is it possible to predict how a court will balance the elements that go into a fair use analysis? Is there a way to define or measure exactly how much of a different aesthetic is required? Moreover, when is a secondary use “derivative,” meaning that the original owner controls the right to make additional works, and when is it fair use?

More on this next time.

March 21, 2023

U.S. law has long grappled with when it’s okay to copy someone else’s work. This is a central tension of copyright law, which is supposed to encourage people to create by ensuring they can get paid for their creations while also allowing others to base new works off of existing ones.

These dueling forces are the subject of the legal doctrine of “fair use,” which is at the heart of a case the U.S. Supreme Court will soon decide. The case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, is being closely watched by artists, collectors and museums.

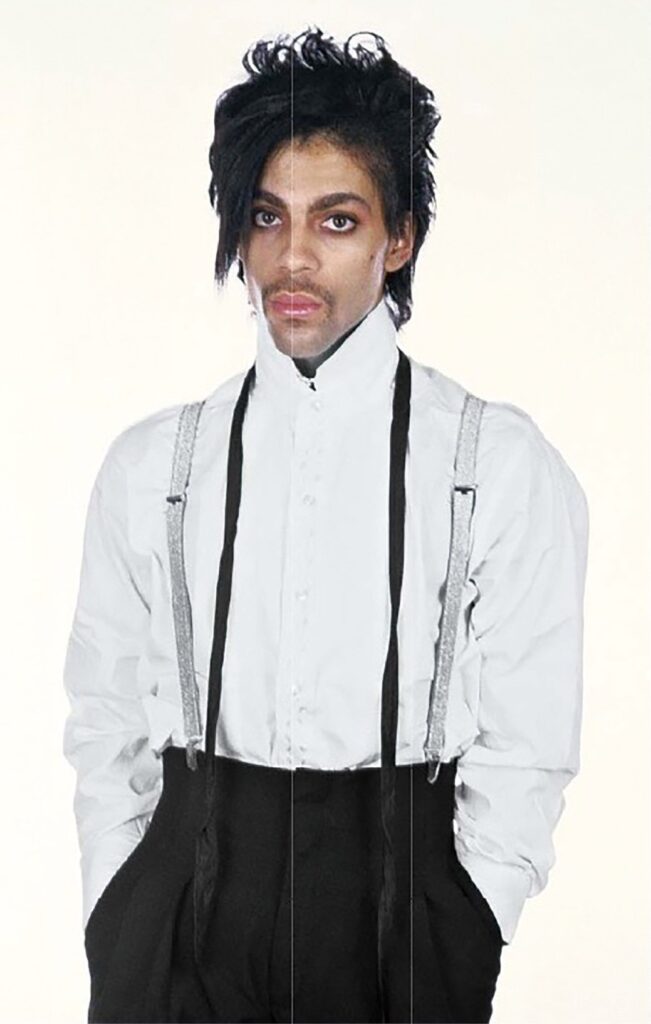

Some background: In 1981, Newsweek hired Lynn Goldsmith, a photographer famous for her album covers and work with rock stars, to photograph the up-and-coming R&B artist Prince. Goldsmith kept this unused outtake for future licensing:

By 1984 Prince was a megastar and Goldsmith licensed the photo to Vanity Fair. This license allowed the magazine to hire an artist to create an illustration based on the photo for a feature story. Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith $400 and commissioned Andy Warhol to make the art.

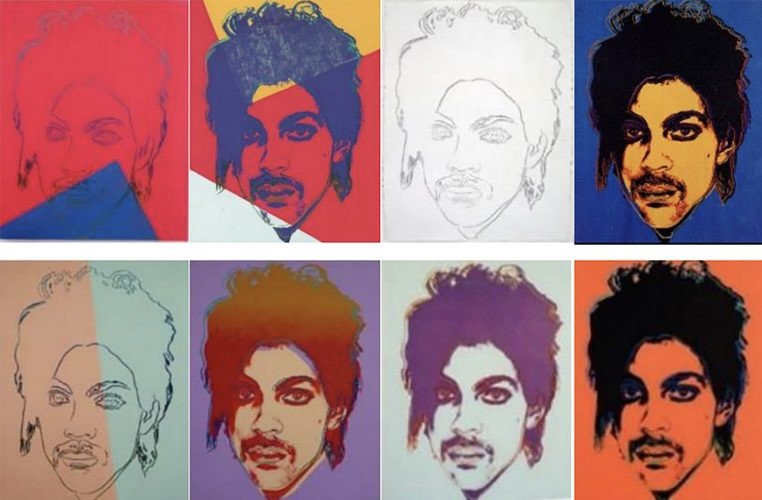

Working from the photo, Warhol created 16 silkscreens, which he copyrighted. Vanity Fair used one for its article. The entire collection became famous in the art world as the Prince Series, and was sold and reproduced for hundreds of millions of dollars.

When Prince died, Condé Nast, which publishes Vanity Fair, paid the Warhol Foundation $10,250 to run one of Warhol’s Prince images on the cover of a tribute issue. The magazine neither credited nor paid Goldsmith.

At that point, Goldsmith learned of the Prince Series and told the Andy Warhol Foundation that the series infringed on her copyright in the photo. The Foundation countered that Warhol had merely used her image of Prince as a building block to create something new: he cropped and resized the original image, changed the tone, lighting and detail, and added colors, shading and outlines over it. The result, according to the Foundation, was a new work that “comments on the manner in which society encounters and consumes celebrity.” The Foundation sued Goldsmith for a declaration of non-infringement or, alternatively, a declaration that the Prince Series constituted fair use. Goldsmith countersued for copyright infringement.

The Federal District Court in Manhattan ruled in favor of the Foundation. It found the Prince Series “transformative” because it communicated a message different from Goldsmith’s original photograph. Thus, according to the District Court, Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo was fair use.

Goldsmith appealed to the Second Circuit which, in August 2021, reversed and found that the Prince Series was “substantially similar” to her original photograph and did not constitute fair use.

In reaching this decision, the Second Circuit reviewed each of the four factors considered in a fair use analysis: the purpose and character of the secondary use; the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount and substantiality of the secondary use; and the impact of the second work on the market for the origins.

The Second Circuit found that the Prince Series was not fair use because both the original photo and the Prince Series share the same purpose — they are both visual art. Moreover, in the Second Circuit’s view, the Prince Series isn’t fair use because it doesn’t obviously comment on or use the original for a different purpose. Rather, the Prince Series merely recast the original work with a new aesthetic.

It also was clearly troubled by the fact that the Prince Series negatively impacted the market for Goldsmith’s original photo and the possible consequences of people avoiding paying artists’ licensing fees by creating stylized derivative images.

As much as the Second Circuit examined how the two works are reasonably perceived, did the fact that Warhol isn’t around to explain his thinking impact the court’s thinking? Maybe, but should this matter?

Perhaps more centrally, how do you figure out what’s a new aesthetic and what’s not? Or, how much of a new aesthetic is necessary to distinguish a work as new?

These are very hard questions to answer and the Supreme Court pushed the parties’ attorneys — especially the Foundation’s attorney — on where to draw the line.

More on how we got here in the next post.

August 11, 2022

The Southern District of Florida recently issued a decision in a case that brands using social media influencers should note. While the decision was not an all out loss for the brand, it did conclude that the brand could be liable if the copyright owner was able to show the brand profited from its social media influencers’ use of copyrighted materials.

By way of background, Universal Music is suing Vital Pharmaceuticals, Inc., which makes an energy drink called Bang, and its owner, Jack Owoc, for copyright infringement. The lawsuit alleges that Bang and Owoc directly infringed on Universal Music’s copyrights with TikTok posts that included Universal Music’s copyrighted music. Universal Music further claims Bang was contributorily and/or vicariously liable for videos posted by social media influencers featuring Bang. In response, Bang and Owoc claimed that the TikTok videos were covered by TikTok’s music licenses and that Bang could not control what its influencers posted to TikTok.

As an introduction (or refresher), direct infringement is where someone uses copyrighted materials that belong to someone else. In contrast, contributory infringement is where someone encourages another to use copyrighted material belonging to a third-party, and vicarious infringement is where a party profits from another’s direct infringement and does not stop that direct infringement.

In support of its claims, Universal Music introduced evidence that Bang encouraged influencers to create and post TikTok videos promoting Bang’s products with Universal Music’s copyrighted works. Universal Music claimed that, because Bang had the power to withhold payment to its influencers, it could control whether influencers used Universal Music’s copyrighted works.

On Universal Music’s motion for summary judgment, the court held that Universal Music established that Bang and Owac directly infringed on its copyrights. Specifically, the court found that Bang and Owac directly copied Universal Music’s copyrighted works.

The court went on to find that Universal Music was not entitled to summary judgment on its claim of contributory infringement as it had not shown that Bang had any input into the music used by its influencers.

The court further concluded that Universal Music established that Bang had sufficient control over its influencers to prevail on a claim of vicarious infringement. Despite this finding, the court denied Universal Music’s motion for summary judgment because Universal Music had not shown that Bang received any financial benefit as a result of its influencers’ posts. As a result, this issue will have to await trial when Universal Music can introduce evidence as to whether Bang benefited.

Despite the fact that this decision was not an all out loss for Bang, brands should definitely keep it in mind when working with influencers.

July 14, 2022

On June 9, 2022, Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Thom Tillis (R-NC), the Chair and Ranking Member of the Senates Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, sent a letter to the Director of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) and the Director of the United States Copyright Office (Copyright Office) asking them to complete a study on various issues related to non-fungible tokens (NFTs). The non-exhaustive list of topics in this letter includes:

- What are the current and future intellectual property and intellectual property-related challenges stemming from NFTs?

- Can NFTs be used to manage IP rights?

- Do current statutory protections for copyright, for example, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, apply to NFT marketplaces, and are they adequate to address infringement concerns?

On July 8, 2022, the PTO and Copyright Office responded to the Senators. In their response, they stated that they would consult with relevant stakeholders and complete the requested study.

While the list provided by the Senators is a good starting place, the fact that they gave the PTO and Copyright Office until June 2023 to complete the study, means that it’s going to be a while until we have any additional information from the PTO and Copyright Office. Moreover, while the PTO and Copyright Office certainly have a role to play here, the legal framework will continue to develop as Courts rule on cases involving NFTs.