Copyright

September 9, 2024

Last week, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed a federal judge’s March 2023 holding that the Internet Archive’s practice of digitizing library books and making them freely available to readers on a strict one-to-one ratio was not fair use. For reasons I’ll get into below, the outcome is pretty unsurprising. It’s also worth looking at because it likely previews some of the arguments we’ll hear in the case between the New York Times and OpenAI (creators of ChatGPT) and Microsoft if (or when) that case makes it to the Second Circuit. (Quick summary of my post on the subject: The New York Times Company filed suit late in December against Microsoft and several OpenAI affiliates, alleging that by using New York Times content to train its algorithms, the defendants infringed on the media giant’s copyrights, among other things.)

First, some background. The Internet Archive is a not-for-profit organization “building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form” whose “mission is to provide Universal Access to All Knowledge.” To achieve this rather lofty goal, the Archive created its Open Library by scanning printed books in its possession or in the possession of a partner library and lending out one digital copy of a physical book at a time, in a system it dubs Controlled Digital Lending.

Enter COVID-19. During the height of the pandemic, when everyone was stuck at home without much to do, the Archive launched the National Emergency Library. This did away with Controlled Digital Lending and allowed almost unlimited access to each digitized book in its collection.

Not surprisingly, book publishers, who sell electronic copies of books to both individuals and libraries, were not thrilled. Four big-time publishers — Hachette, Penguin Random House, Wiley, and HarperCollins — sued the Internet Archive for copyright infringement, targeting both its National Emergency Library and Open Library as “willful digital piracy on an industrial scale.”

The Internet Archive responded that these projects constituted fair use and, therefore, did not infringe on the publisher’s copyrights. To back this up, the Archive claimed it was using technology “to make lending more convenient and efficient” because its work allowed users to do things that were not possible with physical books, such as permitting “authors writing online articles [to] link directly to” a digital book in the Archive’s library. The Archive also insisted its library was not supplanting the market for the publisher’s products.

The District Court rejected these arguments, holding that no case or legal principle supported the Archive’s defense that “lawfully acquiring a copyrighted print book entitles the recipient to make an unauthorized copy and distribute it in place of the print book, so long as it does not simultaneously lend the print book.” The judge also deemed the concept of Controlled Digital Lending “an invented paradigm that is well outside of copyright law.”

In affirming the District Court’s ruling, the Second Circuit Court applied the four-part test for fair use that looks at: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyright work; (3) the portion of the copyrighted work used (as compared to the entirety of the copyrighted work); and (4) the impact of the allegedly fair use on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The first factor — the purpose and character of the use — is broken down into two subsidiary questions: Does the new work transform the original, and is it of a commercial nature or is it for educational purposes? Neither the District Court nor the Court of Appeals bought the Internet Archive’s claim that its Open Library was transformative. The Court of Appeals held that the digital books provided by the Internet Archive “serve the same exact purpose as the original; making the authors’ works available to read.” (The Court of Appeals did find that, as a not-for-profit entity, the Internet Archive’s use of the books was not commercial.)

On the second factor, which is generally unimportant here, the Court of Appeals also found in favor of the publishers. Of greater significance is factor three, which looks at how much of the copyrighted work is at issue. Copying a sentence or a paragraph of a book length work is more likely to be fair use than copying the entire book which, of course, is exactly what the Internet Archive was doing. Again, another win for the publishers.

And arguments on factor four — the impact on the market for the publishers’ products — didn’t work out any better for the Internet Archive. Notably, the Court of Appeals found that the Internet Archive was copying the publishers’ books for the exact same purpose as the original works offered by the publisher, thus naturally impacting their market and value.

So what are the takeaways here as we look ahead to the case between the New York Times and Open AI/Microsoft?

On the one hand, OpenAI/Microsoft have copied entire articles from the Times (and the numerous other plaintiffs that are suing OpenAI and Microsoft), which will hurt OpenAI/Microsoft claims of fair use. Likewise, OpenAI/Microsoft’s fair use arguments won’t get very far if the Times can show that ChatGPT’s works are negatively impacting the market for its work or functioning as a substitute for journalism.

On the other hand, if OpenAI/Microsoft can show that ChatGPT’s output transformed the Times’ content, it may be able to prevail on fair use.

In any event, the case between OpenAI and Microsoft and The New York Times is likely to include a lot more ambiguity than in the Internet Archive matter, with the potential to result in new interpretations of copyright law with massive consequences for media and technology companies worldwide.

August 6, 2024

Everything should be clicking (as it were) for TikTok influencer Sydney Nicole Gifford. She has half a million followers who eat up her posts promoting home and fashion items from Amazon, propelling her to the kind of celebrity that garnered coverage in People for her pregnancy. But alas, Gifford is apparently a little too influential.

She claims fellow TikToker Alyssa Sheil is copying her posts and using Gifford’s visual style to promote the same products! And yes, Gifford is now suing Sheil, in a case that could shake up the world of social media influencers and potentially make it harder for influencers to create content without fear of accusations of copying.

According to the complaint, which was filed in District Court in Texas, Gifford “spends upwards of ten hours a day, seven days a week, researching unique products and services that may fit her brand identity, testing and assessing those products and services, styling photos and videos promoting such products and editing posts…” for social media. As a result, according to the complaint, “Sydney has become well-known for promoting certain goods from Amazon, including household goods, apparel, and accessories, through original photo and video works…”

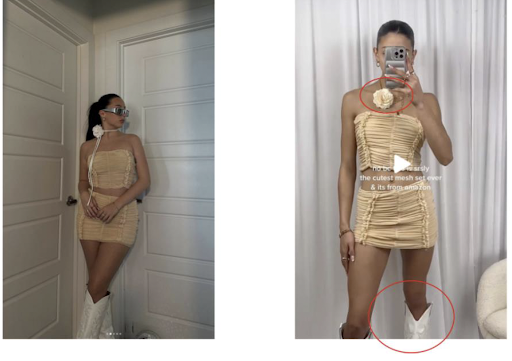

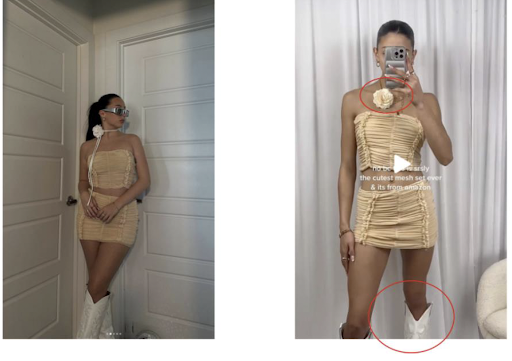

The lawsuit goes on to allege that defendant Sheil “replicated the neutral, beige, and cream aesthetic of [Gifford’s] brand identity, featured the same or substantially [the same] Amazon products promoted by [Gifford], and contained styling and textual captions replicating those of [Gifford’s] posts.” It says at least 40 of Sheil’s posts feature “identical styling, tone, camera angle and/or text,” to Sydney’s. Here’s a pretty obvious one, with Gifford on the left and Sheil on the right.

In the suit, Gifford is claiming, among other things, trade dress infringement, violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, copyright infringement (she has registered copyrights for some of her posts and videos), and unfair competition.

Does Gifford have a case? Here’s what I think:

- To prevail on the claim for infringement of her trade dress Gifford will have to establish, at a minimum, that consumers associate her “aesthetic” with her. That may be difficult because, at least to my eye, the style of Gifford’s posts doesn’t seem wildly different from a lot of other influencers. (I am so not her target audience and I’m doing my best not to dunk on her “aesthetic,” but I have to put “aesthetic” in quotes to convey my eyeroll.)

- The claim under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act is based on the fact that Sheil removed Gifford’s name or social media handle from posts. This is, shall we say, a novel argument given that the intent of the DMCA is to prevent people from circumventing digital rights management software. This is not that. At all.

- The copyright claim is going to raise a lot of questions about exactly how original these social media posts are and, as a result, how much protection under copyright law they are entitled to. Gifford and other social media influencers might find out that they don’t like the answer to this question.

- If Gifford is able to establish that consumers associate her “aesthetic” with her, she could win the battle… but lose the war because it might open her up to lawsuits by other influencers who claim that she copied their look.

Meanwhile, Sheil has asked the Court to dismiss Gifford’s case.

Thinking more broadly, a decision or decisions on the copyright claim could have implications for appropriation artists and others who closely copy another creator’s work. Which is one reason it will be fascinating to see how this plays out. And yes, I know I often end these posts saying something like that. Because it’s true! This case, as with so many IP lawsuits lately, especially those that involve AI, are all going where no court has gone before (or even imagined possible ten years ago). Every one of these potential decisions could have massive socioeconomic impact, with a real effect on how a lot of people earn a living and how the rest of us spend a lot (probably too much) of our time.

May 29, 2024

If you’re into hip hop, you’re probably familiar with a photograph of rapper The Notorious B.I.G., a/k/a Biggie Smalls, looking contemplative behind designer shades with the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in the distance behind him. However, you might not know this well-known portrait has been the subject of litigation for the past five years and that litigation settled just before a trial was supposed to start earlier this year.

Photographer Chi Modu snapped the picture (the “Photo”) in 1996, originally for the cover of The Source hip hop monthly. However, after the magazine used another image, and Biggie was killed a year later, Modu began licensing the image to various companies, including Biggie’s heirs’ own marketing company. The Photo became famous and, after the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001, what is now commonly called “iconic.”

There was no beef (do people still say that?) between Modu and Biggie’s heirs until 2018 when, according to an attorney for Chi Modu’s widow (the photographer himself passed away in 2021), Modu tried to negotiate increased licensing fees with Notorious B.I.G. LLC (“BIG”), which owns and controls the intellectual property rights of the late rapper’s estate.

Apparently, Modu and BIG weren’t able to reach an agreement because BIG brought suit against Modu and a maker of snowboards bearing the image, asserting claims for federal unfair competition and false advertising, trademark infringement, violation of state unfair competition law and violation of the right of publicity.

In a countersuit, Modu asserted his copyright in the Photo of Biggie preempted all of BIG’s claims. Modu argued that BIG’s claims were nothing more than an attempt to interfere with his right to reproduce and distribute the Photo, as permitted under Section 301 of the Copyright Act.

In December 2021, BIG sought a preliminary injunction barring Modu from selling merchandise including skateboards, shower curtains and NFTs incorporating the Photo, claiming these uses violated its exclusive control of Biggie’s right of publicity. (BIG had previously settled with the snowboard manufacturer.)

In June 2022, the Court granted the injunction in part, concluding that the sale of skateboards and shower curtains was not preempted by the Copyright Act as they did not involve the sale of the Photo itself but rather items featuring the Photo. In its order, it prohibited Modu’s estate from selling merchandise featuring the Photo or licensing the Photo for such use. However, the Court permitted Modu’s estate to continue selling reproductions of Modu’s photo as “posters, prints and Non-Fungible Tokens (‘NFTs’).” The Court found that the posters, prints and NFTs were “within the subject matter of the Copyright Act [as t]hey relate to the display and distribution of the copyrighted works themselves, without a connection to other merchandise or advertising.”

This decision follows a line of cases that distinguish between the exploitation of a copyright and the sale of products “offered for sale as more than simply a reproduction of the image.” In the former situation, a copyrighted work will take precedence over a right of publicity claim. In the latter, where the products feature something more than just the copyrighted work, a right of publicity claim is likely to prevail.

Not surprisingly, given the risks for both sides, the case settled just prior to the start of the trial. Although the contours of the settlement were not made public, presumably it allowed Modu’s estate to continue selling the Photo as posters of it remain available for purchase on the photographer’s website.

January 16, 2024

I closed out 2023 by writing about one lawsuit over AI and copyright and we’re starting 2024 the same way. In that last post, I focused on some of the issues I expect to come up this year in lawsuits against generative AI companies, as exemplified in a suit filed by the Authors Guild and some prominent novelists against OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT). Now, the New York Times Company has joined the fray, filing suit late in December against Microsoft and several OpenAI affiliates. It’s a big milestone: The Times Company is the first major U.S. media organization to sue these tech behemoths for copyright infringement.

As always, at the heart of the matter is how AI works: Companies like OpenAI ingest existing text databases, which are often copyrighted, and write algorithms (called large language models, or LLMs) that detect patterns in the material so that they can then imitate it to create new content in response to user prompts.

The Times Company’s complaint, which was filed in the Southern District of New York on December 27, 2023, alleges that by using New York Times content to train its algorithms, the defendants directly infringed on the New York Times’ copyright. It further alleges that the defendants engaged in contributory copyright infringement and that Microsoft engaged in vicarious copyright infringement. (In short, contributory copyright infringement is when a defendant was aware of infringing activity and induced or contributed to that activity; vicarious copyright infringement is when a defendant could have prevented — but didn’t — a direct infringer from acting, and financially benefits from the infringing activity.) Finally, the complaint alleges that the defendants violated the Digital Millennium Copyright Act by removing copyright management information included in the New York Times’ materials, and accuses the defendants of engaging in unfair competition and trademark dilution.

The defendants, as always, are expected to claim they’re protected under “fair use” because their unlicensed use of copyrighted content to train their algorithms is transformative.

What all this means is that while 2023 was the year that generative AI exploded into the public’s consciousness, 2024 (and beyond) will be when we find out what federal courts think of the underlying processes fueling this latest data revolution.

I’ve read the New York Times’ complaint (so you don’t have to) and here are some takeaways:

- The Times Company tried (unsuccessfully) to negotiate with OpenAI and Microsoft (a major investor in OpenAI) but were unable to reach an agreement that would “ensure [The Times] received fair value for the use of its content.” This likely hurts the defendants’ claims of fair use.

- As in the other lawsuits against OpenAI and similar companies, there’s an input problem and an output problem. The input problem comes from the AI companies ingesting huge amounts of copyrighted data from the web. The output problem comes from the algorithms trained on the data spitting out material that is identical (or nearly identical) to what they ingested. In these situations, I think it’s going to be rough going for the AI companies’ fair use claim. However, they have a better fair use argument where the AI models create content “in the style of” something else.

- The Times Company’s case against Microsoft comes, in part, from the fact that Microsoft is alleged to have “created and operated bespoke computing systems to execute the mass copyright infringement . . .” described in the complaint.

- OpenAI allegedly favored “high-quality content, including content from the Times” in training its LLMs.

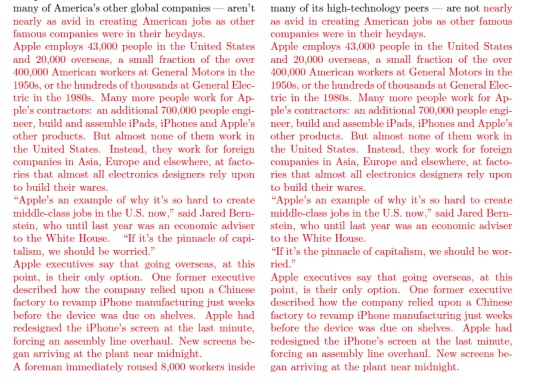

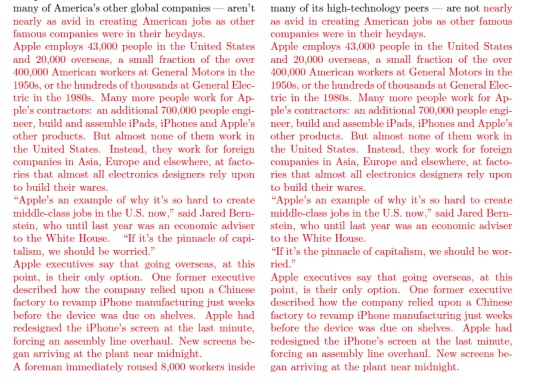

- When prompted, ChatGPT can regurgitate large portions of the Times’ journalism nearly verbatim. Here’s an example taken from the complaint showing the output of ChatGPT on the left in response to “minimal prompting,” and the original piece from the New York Times on the right. (The differences are in black.)

- According to the New York Times this content, easily accessible for free through OpenAI, would normally only be available behind their paywall. The complaint also contains similar examples from Bing Chat (a Microsoft product) that go far beyond what you would get in a normal search using Bing. (In response, OpenAI says that this kind of wholesale reproduction is rare and is prohibited by its terms of service. I presume that OpenAI has since fixed this issue, but that doesn’t absolve OpenAI of liability.)

- Because OpenAI keeps the design and training of its GPT algorithms secret, the confidentiality order here will be intense because of the secrecy around how OpenAI created its LLMs.

- While the New York Times Company can afford to fight this battle, many smaller news organizations lack the resources to do the same. In the complaint, the Times Company warns of the potential harm to society of AI-generated “news,” including its devastating effect on local journalism which, if the past is any indication, will be bad for all of us.

Stay tuned. OpenAI and Microsoft should file their response, which I expect will be a motion to dismiss, in late-February or so. When I get those, I’ll see you back here.

December 19, 2023

This year has brought us some of the early rounds of the fights between creators and AI companies, notably Microsoft, Meta, and OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT). In addition to the Hollywood strikes, we’ve also seen several lawsuits between copyright owners and companies developing AI products. The claims largely focus on the AI companies’ creation of “large language models” or “LLMs.” (By way of background, LLMs are algorithms that take a large amount of information and use it to detect patterns so that it can create its own “original” content in response to user prompts.)

Among these cases is one filed by the Authors Guild and several prominent writers (including Jonathan Franzen and Jodi Picoult) in the Southern District of New York. It alleges OpenAI ingested large databases of copyrighted materials, including the plaintiffs’ works, to train their algorithms. In early December, the plaintiffs amended their complaint to add Microsoft as a defendant alleging that Microsoft knew about and assisted OpenAI in its infringement of the plaintiffs’ copyrights.

Because it is the end of the year, here are five “things to look for in 2024” in this case (and others like it):

- What will defendants argue on fair use and how will the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Goldsmith impact this argument? (In 2023 the SCOTUS ruled that Andy Warhol’s manipulation of a photograph by Lynn Goldsmith was not transformative enough to qualify as fair use.)

- Does the fact that the output of platforms like ChatGPT isn’t copyrightable have any impact on the fair use analysis? The whole idea behind fair use is to encourage subsequent creators to build on the work of earlier creators, but what happens to this analysis when the later “creator” is merely a computer doing what it was programmed to do?

- Will the fact that OpenAI recently inked a deal with Axel Springer (publisher of Politico and Business Insider) to allow OpenAI to summarize its news articles as well as use its content as training data for OpenAI’s large language models affect OpenAI’s fair use argument?

- What impact, if any, will this and other similar cases have on the business model for AI? Big companies and venture capital firms have invested heavily in AI, but if courts rule they must pay authors and other creators for their copyrighted works it dramatically changes the profitability of this model. Naturally, tech companies are putting forth numerous arguments against payment, including how little each individual creator would get considering how large the total pool of creators is, how it would curb innovation, etc. (One I find compelling is the idea that training a machine on copyrighted text is no different from a human reading a bunch of books and then using the knowledge and sense of style gained to go out and write one of their own.)

- Is Microsoft, which sells (copyrighted) software, ok with a competitor training its platform on copyrighted materials? I’m guessing that’s probably not ok.

These are all big questions with a lot at stake. For good and for ill, we live in exciting times, and in the arena of copyright and IP law I guarantee that 2024 will be an exciting year. See you then!